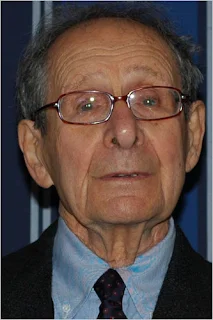

(October 29, 1917 – April 21, 2011) |

Biography

Garfinkel was raised in Newark, New Jersey, in the years preceding the Great Depression. His father, a furniture dealer, had hoped his son would follow him into the family business. When the time arrived for Harold to attend college, he studied accounting at the University of Newark. In the summer following graduation he worked as a volunteer at a Quaker work camp in Cornelia, Georgia. This was a horizon-broadening experience for Garfinkel. He worked there with students with a variety of interests and backgrounds, and this led him to decide to take up sociology as a career.[2] In the fall of that same year, Garfinkel enrolled in the graduate program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he completed his Masters in 1942. With the onset of World War II, he was drafted into the Army Air Corps and served as a trainer at a base in Florida. As the war effort wound down he was transferred to Gulfport, Mississippi. There he met Arlene Steinbach who was to become his wife and life-long partner.As a student at Chapel Hill, he was introduced to the writings of Talcott Parsons. In 1946 Garfinkel went to study with Parsons at the newly-formed Department of Social Relations at Harvard University. He also became acquainted, during this period, with a number of European scholars who had recently immigrated to the U.S. These would include Aron Gurwitsch, Felix Kaufmann, and Alfred Schütz, who introduced the young sociologist to newly-emerging ideas in social theory, psychology and phenomenology. While still a student at Harvard, Garfinkel was invited by the sociologist Wilbert Ellis Moore to work on the Organizational Behavior Project at Princeton University. Garfinkel was responsible for organizing two conferences in conjunction with this project. It brought him in contact with some of the most prominent scholars of the day in the behavioral, informational, and social sciences including: Gregory Bateson, Kenneth Burke, Paul Lazarsfeld, Frederick Mosteller, Philip Selznick, Herbert Simon, and John von Neumann.[3] Garfinkel's dissertation, "The Perception of the Other: A Study in Social Order," was completed in 1952.

After leaving Harvard, he worked on two large research projects, one conducting leadership studies under the auspices of the Personnel Research Board at Ohio State University and the American Jury Project for which he did fieldwork in Arizona. In 1954 he joined the sociology faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles. During the period 1963-64 he served as a Research Fellow at the Center for the Scientific Study of Suicide.[4] Garfinkel spent the ’75-’76 school year at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences and, in 1979-1980, was a visiting fellow at Oxford University. He retired from UCLA in 1987.

The Roots of Ethnomethodology

Parsons sought to offer a solution to the problem of social order (i.e., How do we account for the order that we witness in society?) and, in so doing, provide a disciplinary foundation for research in sociology. Drawing on the work of earlier social theorists (Marshall, Pareto, Durkheim, Weber), Parsons postulated that all social action could be understood in terms of an “action frame” consisting of a fixed number of elements (an agent, a goal or intended end, the circumstances within which the act occurs, and its “normative orientation”).[5] Agents make choices among possible ends, alternative means to these ends, and the normative constraints that might be seen as operative. They conduct themselves, according to Parsons, in a fashion “analogous to the scientist whose knowledge is the principal determinant of his action.”[6] Order, by this view, is not imposed from above, but rather arises from rational choices made by the actor. Parsons sought to develop a theoretical framework for understanding how social order is accomplished through these choices.Schütz, like Parsons, was concerned with establishing a sound foundation for research in the social sciences. He took issue, however, with the Parsonsian assumption that actors in society always behave rationally. Schütz made a distinction between reasoning in the ‘natural attitude’ and scientific reasoning.[7] The reasoning of scientists builds upon everyday commonsense, but, in addition, employs a “postulate of rationality.”[8] This imposes special requirements on their claims and conclusions (e.g., application of rules of formal logic, standards of conceptual clarity, compatibility with established scientific ‘facts’). This has two important implications for research in the social sciences. First, it is inappropriate for sociologists to use scientific reasoning as a lens for viewing human action in daily life, as Parsons had proposed, since they are distinct kinds of rationality. On the other hand, the traditionally assumed discontinuity between the claims of science and commonsense understandings is dissolved since scientific observations employ both forms of rationality.[9] This raises a flag for researchers in the social sciences, since these disciplines are fundamentally engaged in the study of the shared understandings that underlie the day-to-day functioning of society. How can we make detached, objective claims about everyday reasoning, if our conceptual apparatus is hopelessly contaminated with commonsense categories and rationalities?

Accepting Schütz’s critique of the Parsonian program, Garfinkel sought to find another way of addressing the Problem of Social Order. He wrote, “Members to an organized arrangement are continually engaged in having to decide, recognize, persuade, or make evident the rational, i.e., the coherent, or consistent, or chosen, or planful, or effective, or methodical, or knowledgeable character of [their activities]”.[10] On first inspection, this might not seem very different from Parsons’ proposal. Their views on rationality, however, are not compatible. For Garfinkel, society’s character is not dictated by an imposed standard of rationality, either scientific or otherwise. Instead, rationality is itself produced as a local accomplishment in, and as, the very ways that society’s members craft their moment-to-moment interaction. He writes:

Instead of the properties of rationality being treated as a methodological principle for interpreting activity, they are to be treated only as empirically problematical material. They would have the status of data and would have to be accounted for in the same way that the more familiar properties of conduct are accounted for.[11]

Social order arises in the very ways that participants conduct themselves together. The sense of a situation arises from their interactions. Garfinkel writes, “any social setting [can] be viewed as self-organizing with respect to the intelligible character of its own appearances as either representations of or as evidences-of-a-social-order.”[12] The orderliness of social life, therefore, is produced through the moment-to-moment work of society’s members and ethnomethodology’s task is to explicate just how this work is done.A vital thread throughout Garfinkel’s inquiries was derived from Aron Gurwitsch’s studies of the phenomenal field. This interest led Garfinkel to investigate many non-concept driven modes of local organization, investigations that may be witnessed in his studies of the legally blind woman Helen,[13] inverting lenses,[14] freeway traffic flow, and pedestrian crossings. Ethnomethodology has distanced itself from many of the customary epistemologies of rationalism, positivism, and concept-driven inquiries, and has placed increasing emphasis on the practical ways that parties concert their activities in local settings. This interest is derived from both Schütz and Gurwitsch, but the embodied analyses of Maurice Merleau-Ponty[15] also offered important direction.

Garfinkel regarded indexical expressions as key phenomena. Words like here, now, and me shift their meaning depending on when and where they are used. Philosophers and linguists refer to such terms as indexicals because they point into (index) the situational context in which they are produced. One of Garfinkel’s contributions was to note that such expressions go beyond "here", "now," etc. and encompass any and all utterances that members of society produce. As Garfinkel specified, “The demonstrably rational properties of indexical expressions and indexical actions [are] an ongoing achievement of the organized activities of everyday life”.[16] The pervasiveness of indexical expressions and their member-ordered properties mean that all forms of action provide for their own understandability through the methods by which they are produced.[17] That is, action has the property of reflexivity whereby such action is made meaningful in the light of the very situation within which it is produced.

The contextual setting, however, should not be seen as a passive backdrop for the action. Reflexivity means that members shape action in relation to context while the context itself is constantly being redefined through action.[18] The initial insight into the importance of reflexivity occurred during the study of juror’s deliberations, wherein what jurors had decided was used by them to reflexively organize the plausibility of what they were deciding. Other investigations revealed that parties did not always know what they meant by their own formulations; rather, verbal formulations of the local order of an event were used to collect the very meanings that gave them their coherent sense. Garfinkel declared that the issue of how practical actions are tied to their context lies at the heart of ethnomethodological inquiry. Using professional coffee tasting as an illustration here, taste descriptors do not merely describe but also direct the tasting of a cup of coffee; hence, a descriptor is not merely the causal result of what is tasted, as in:

coffee ⇒ taste descriptor

Nor is it an imperialism of a methodology:taste descriptor ⇒ coffee

Rather, the description and what it describes are mutually determinative:taste descriptor ⇔ coffee

The descriptors operate reflexively by finding in the coffee what they mean, and each is used to make the other more explicit. Much the same may be said about rules-in-games or the use of accounts in ordinary action.[19] This reflexivity of accounts is ubiquitous, and its sense has nearly nothing to do with how the term “reflexivity” is used in analytic philosophy, in “reflexive ethnographies” that endeavor to expose the influence of the researcher in organizing the ethnography, or the way many social scientists use "reflexivity" as a synonym for "self-reflection." For ethnomethodology reflexivity is an actual, unavoidable feature of everyone’s daily life.Garfinkel has frequently illustrated ethnomethodological analysis by means of the illustration of service lines.[20] Everyone knows what it is like to stand in a line. Queues are a part of our everyday social life; they are something within which we all participate as we carry out our everyday affairs. We recognize when someone is waiting in a line and, when we are "doing" being a member of a line, we have ways of showing it. In other words, lines may seem impromptu and routine, but they exhibit an internal, member-produced embodied structure. A line is “witnessably a produced social object;”[21] it is, in Durkheimian terms, a “social fact.” Participants' actions as "seeably" what they are (such as occupying a position in a queue) depend upon practices that the participant engages in in relation to others' practices in the proximate vicinity. To recognize someone as in a line, or to be seen as "in line" ourselves requires attention to bodily movement and bodily placement in relation to others and to the physical environment that those movements also constitute. This is another sense that we consider the action to be indexical—it is made meaningful in the ways in which it is tied to the situation and the practices of members who produce it. The ethnomethodologist's task becomes one of analyzing how members' ongoing conduct is a constituent aspect of this or that course of action. Such analysis can be applied to any sort of social matter (e.g., being female, following instructions, performing a proof, participating in a conversation). These topics are representative of the kinds of inquiry that ethnomethodology was intended to undertake.

Ethnomethodology was not designed to supplant the kind of formal analysis recommended by Parsons. Garfinkel stipulated that the two programs are “different and unavoidably related.”[22] Both seek to give accounts of social life, but ask different kinds of questions and formulate quite different sorts of claims. Sociologists operating within the formal program endeavor to produce objective (that is to say, non-indexical) claims similar in scope and to those made in the natural sciences. To do so, they must employ theoretical constructs that pre-define the shape of the social world. Unlike Parsons, and other social theorists before and since, Garfinkel’s goal was not to articulate yet another explanatory system. He expressed an “indifference” to all forms of sociological theorizing.[23] Instead of viewing social practice through a theoretical lens, Garfinkel sought to explore the social world directly and describe its autochthonous workings in elaborate detail. Durkheim famously stated, "[t]he objective reality of social facts is sociology’s fundamental principle."[24] Garfinkel substituted ‘phenomenon’ for ‘principle’, signaling a different approach to sociological inquiry.[25] The task of sociology, as he envisions it, is to conduct investigations into just how Durkheim’s social facts are brought into being. The result is an “alternate, asymmetric and incommensurable” program of sociological inquiry.[26]

No comments:

Post a Comment