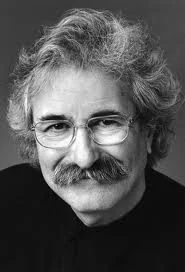

Andrew Michael Geller was an

American

architect, painter and graphic designer widely known for his

uninhibited, sculptural beach houses in the coastal regions of New York,

New Jersey and Connecticut during the 1950s and 60s—and for his

indirect role in the 1959

Kitchen Debate between

Richard Nixon (then Vice President) and Soviet Premier

Nikita Khrushchev, which began at an exhibit Geller had helped design for the

American National Exhibition in Moscow died from kidney failure he was 87..

Geller worked with the prominent firm of American industrial and graphic designer

Raymond Loewy where his projects ranged widely—from the design of shopping centers and department stores across the United States, to the

Windows on the World restaurant atop the

World Trade Center[1] and the logo of New York-based department store

Lord and Taylor[1][2]

After designing a beach house for Loewy's director of public relations,

[3] Geller was featured in the

New York Times and began receiving notoriety for his own work. Between 1955 and 1974,

[4] Geller produced a series of modest but distinctive vacation homes, many published in popular magazines including

Life,

Sports Illustrated, and

Esquire.

[3]

On his death in 2011, the

New York Times said Geller "helped bring modernism to the masses."

[5]

Background

| “ |

It’s one of the first

lessons I ever was taught.

The thing you produce ought

to be compatible with what’s there.

It should live with it both in

scale and some sort of human factor.

– Andrew Geller [6] |

” |

|

Geller was born in Brooklyn on April 17, 1924 to Olga and Joseph

Geller, an artist and sign painter who had emigrated from Hungary in

1905.

[7] Architectural historian

Alastair Gordon reported that as a sign painter Joseph Geller designed the logo for

Boar's Head Provision Company, still in use today.

[3]

Geller studied drawing with his father,

[3] and the attended art classes at the

Brooklyn Museum. A 1938 painted self-portrait won him a scholarship to the

New York High School of Art and Music (1939),

[3] and he subsequently studied architecture at

Cooper Union,

[5] where he took drawing class with Robert Gwathmey, father of architect

Charles Gwathmey.

[3]

Geller later worked as a naval architect for the United States Maritime

Commission designing tanker hulls and interiors (1939–42).

During World War II, Geller served in the

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

(1942–45) and was inadvertently exposed to a toxic chemical agent,

suffering medical consequences for the remainder of his life.

[3] Geller married Shirley Morris (a painter)

[8] in 1944. The couple lived in

Northport, New York and together had a son, Gregg Geller (formerly catalog executive at

RCA,

CBS and

Warner Bros.)

[9] and a daughter, Jamie Geller Dutra

[5] (formerly interior designer at

Loewy/Snaith).

[10]

Prior to his death in December 2011 in

Syracuse, Geller lived in

Spencer, New York.

[5]

Career with Loewy

After reading in Life magazine of

Raymond Loewy's diverse and comprehensive career,

[3] Geller began what became a career (variously reported as 28

[8] or 35

[11] years) at Raymond Loewy Associates — later known as Raymond Loewy/William Snaith Inc. or simply Loewy/Snaith.

Geller went on to carry various titles at Loewy/Snaith, including

'head of the New York City architecture department', 'vice president'

and 'director of design,'

[8] — working on notable projects including the interiors and garden (with

Isamu Noguchi) for the glass-and-metal

Lever House.

[7] At Loewy/Snaith, Geller also designed shopping centers and department stores across the United States,

[7] notably for

Macy's,

Lord & Taylor,

Wanamaker's,

Bloomingdales,

Apex Department Stores[12] and

Daytons — as well as work for

Bell Telephone, and the Worlds Fair Beirut U.S. Pavilion (year unknown).

-

- See: Rendering for Apex Department Stores, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Andrew Geller

Geller left Loewy/Snaith in 1976. It has been reported that at some point in his career, Geller designed the

Quiet House for a Dallas, Texas consortium, the all-aluminum

Easy Care Home for the Aluminum Association of America, and the

Vacation House System.[3]

In 2009, the city of

Stamford, Connecticut listed the 150,000 square foot

Lord & Taylor

at 110 High Ridge Road on the state's list of landmark buildings —

after the building had been inadvertently made more prominent by the

razing of adjacent trees.

[13] Geller had designed the three-story building in 1969 while with Loewy/Snaith.

[14] Richard Longstreth, director of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at

George Washington University,

said the store's case for preservation was “quite straightforward,

based on the significance of the company it has housed, the nature of

its siting, the firm that designed the building, and as a now rare

survivor of its type."

[15]

-

- See: Lord & Taylor, Stamford, CT, 1969, Andrew Geller

- See: Rendering, Lord & Taylor, Stamford, CT, Andrew Geller

Kitchen Debate and Leisurama

Main article:

Kitchen Debate

In 1959, as vice president of the Housing and Home Components

department at Loewy/Snaith, Geller was the design supervisor for the

exhibition, the "Typical American House," built at the

American National Exhibition in Moscow. The exhibition home largely replicated a home previously built at 398 Townline Road

[16] in

Commack, New York,

which had been originally designed by Stanley H. Klein for a Long

Island-based firm, All-State Properties (later known as Sadkin

enterprises),

[17] headed by developer Herbert Sadkin.

[18][19] To accommodate visitors to the exhibition, Sadkin hired Loewy's office to modify Klein's floor plan.

[16] Geller supervised the work, which "split" the house, creating a way for large numbers of visitors to tour the small house

[16] and giving rise to its nickname, Splitnik.

[16]

-

- See: Geller's "split" home at the American National Exhibition

- See: 398 Townline Road, Commack, New York, designed by Stanley H. Klein

- 40°51′40.02″N 73°17′25.77″E

Subsequently,

Richard Nixon (then Vice President) and Soviet Premier

Nikita Khrushchev on July 24, 1959 began what became known as the

Kitchen Debate

— a debate over the merits of capitalism vs. socialism, with Khrushchev

saying Americans could not afford the luxury represented by the

"Typical American House".

[7] Tass, the Soviet news agency said:

"There

is no more truth in showing this as the typical home of the American

worker than, say, in showing the Taj Mahal as the typical home of a

Bombay textile worker."[16]

The temporary 'Typical American House' exhibit was demolished, and the developer hired

William Safire as the company's marketing agent.

[16] All-State later hired Loewy and Geller to design

Leisurama, homes marketed at Macy's and built on Long Island — leveraging the press coverage from the Russian exhibition.

[16]

Solo career

Geller became known for a number of homes in

New England that he designed while moonlighting at Loewy/Snaith,

[3] with the encouragement of Loewy and Snaith.

[8]

The houses each had an abstract sculptural quality; a 1999 New York

Times article called the homes "eccentrically free-form and

eye-grabbing."

[7] Another article called the homes "ingenious wooden spacecraft."

[20] Another described the houses as "quirky, tiny, site-specific."

[8] Geller himself gave the houses nicknames such as the

Butterfly, the

Box Kite,

Milk Carton and Grasshopper.

[3]

Geller's work met a varied reception. Mark Lamster, writing for

Design Observer,

described Geller's Long Island house designs as "inexpensive and modest

homes with playful shapes that radiated a sense of post-war optimism."

[21] His 1966 design for the Elkin House in

Sagaponack, New York, which he called

Reclining Picasso was described as "an angular mess" in a 2001

New York Times book review.

[22]

-

- See: Andrew Geller design sketch

- See: Andrew Geller design sketch

Examples of Geller's idiosyncratic home designs include the 1955

Reese House for Elizabeth Reese in Sagaponack, New York

[3] — an

A-Frame house that popularized the construction method after it was featured appeared on the cover of the

New York Times

as well as in the newspaper's real estate section of the May 5, 1957

edition. Reese, the client, was at the time the director of public

relations at Loewy's office, and she publicized Geller's work — with

John Callahan of the New York Times writing several articles on his

work.

[3]

The Pearlroth House in Westhampton, of 1959, consists of a pair of diamond-shaped structures.

[23] When the 600square foot Pearlroth home was slated for demolition in 2006, it was called an "icon of Modernism."

[24]

The house — which featured two boxes rotated 45 degrees in a

distinctive shape — was eventually relocated to be restored as a public

museum.

[24]

Architectural historian Alastair Gordon said the house "is one of the

most important examples of experimental design built during the postwar

period – not just on Long Island but anywhere in the United States. It

is witty, bold and inventive."

In 1958, Geller designed a beach house for bachelors. The

Esquire Weekend House could be delivered to any location to be constructed on stilts.

[3] Alastair Gordan, architectural historian, called the one-room house a "

reducto ad absurdum version of the post-war weekend aesthetic."

[3]

-

- See: The Esquire Weekend House, rendering by Andrew Geller

Publicity

Geller's architectural designs on Long Island were featured in a 1999 exhibition called

Weekend Utopia: The Modern Beach House on Eastern Long Island, 1960–1973, at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York

[20] — and in 2005 at an exhibit entitled

Imagination: The Art and Architecture of Andrew Geller at New York's

Municipal Art Society.

[25]

Geller's grandson, Jake Gorst, wrote, produced and directed a 2005

[26]

documentary about his grandfather's work on the Leisurama homes. Since

2011, Gorst has actively sought to preserve the archives of Geller's

works, including drawings, models and film recordings

[27] — having used

Kickstarter to help

finance the archival work.

Geller's Long Island Homes were subject of the 2003 book

Beach Houses: Andrew Geller. The Macy's homes were the subject of the 2008 book

Leisurama Now: The Beach House for Everyone, by Paul Sahre. In 2001, his Pearlroth house was named one of the "10 Best Houses in the Hamptons."

[28]

To see more of who died in 2011

click here