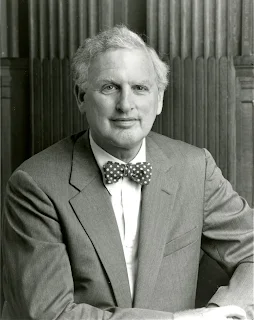

Russell Garcia,

QSM [1] was a composer and arranger who wrote a wide variety of music for screen, stage and broadcast.

Garcia was born in

Oakland, California, but was a longtime resident of

New Zealand.

Self-taught, his break came when he substituted for an ill colleague on

a radio show. Subsequently, he went on to become composer/arranger at

NBC Studios for such television shows as

Rawhide 1962and

Laredo, 1965–67,

MGM and

Universal Studios and films like the

George Pal, MGM films,

The Time Machine (1960) and

Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), as well as his orchestrated themes for

Father Goose (1964) and

The Benny Goodman Story (1956). He collaborated with many musical and Hollywood stars -

Ella Fitzgerald,

Louis Armstrong,

Anita O’Day,

Mel Torme,

Julie London,

Oscar Peterson,

Stan Kenton,

Maynard Ferguson,

Walt Disney,

Orson Welles,

Jane Wyman,

Ronald Reagan,

Andy Williams,

Judy Garland,

Henry Mancini, and

Charlie Chaplin making arrangements and conducting orchestras as needed.

[2] Russ loved to ski so he would write on-site scores to ski-content films.'

(April 12, 1916 - November 19, 2011)

Personal life

One of five brothers, he grew up in what he said was an “ordinary”

household where music was something that came out of the radio.

[2] When his family noticed the five-year-old Russ standing by the radio every Sunday morning waiting for the

New York Philharmonic to come on, it was obvious the child had a special interest in music. One of his brothers presented him with an old

cornet

he bought for $5, which Russ taught himself to play. In school he

started a jazz band to play his new horn, and ended up using the band as

an outlet for his compositions and arrangements of standards – all

self-taught. “I’ve been able to read music since I was little,” he says.

“I don’t know how, because I had lessons only when I went to high

school. Call it instinct, call it a gift, I’ve never questioned my

musical ability. I’m thankful for it. If I take up a sheet of manuscript

paper and a pen there’s a whole orchestra playing in my head. At times I

can’t write quickly enough to keep up with what’s flowing out of me.”

Garcia and his wife Gina Mauriello Garcia, a published author and

singer-lyricist-writer in her own right, became members of the

Bahá'í Faith in 1955.

[3]

In 1966, at the height of his career they sold their home and

possessions, bought a boat, and on 1 June set sail. The couple knew

nothing about sailing and his wife did not know how to swim and the

early arrival of

Hurricane Alma

forced them to return with damage after only two days at sea. It was

December before the boat was finally repaired and they set forth once

again. This time they reached Nassau without any further complications

and spent several years as "travel-teachers" for the Bahá'ís as they

went around the world to places like the

Galapagos Islands,

Haiti,

Cuba,

Jamaica,

Tahiti and the

Marquesas Islands.

When they reached

Fiji in 1969, some musicians from

Auckland, New Zealand

invited Garcia to do some live concerts, radio and television shows and

to lecture at the various universities around the country on behalf of

the New Zealand Broadcasting Commission and Music Trades Association.

Russell, finished with his lectures and concerts and on advice of

friends, drove up to the

Bay of Islands in the north of

North Island.

Garcia and his wife fell in love with the location and bought a house

on the waters edge of Tangitu Bay in the Te Puna Inlet, east of the

Purerua Peninsula near

Kerikeri.

[2]

They spent many years there but have moved into Kerikeri, and still

working regularly, Garcia continues to compose and arrange both in the

U.S. and around the world, including one of his most recent projects

being his and Gina’s first opera,

The Unquenchable Flame.

Together, the Garcias also volunteer their services regularly to teach

primary school children in New Zealand about virtues through the use of

songs, raps, stories, games and creative exercises.

[2]

Events and awards

Memorial Day weekend, 2003, Russell Garcia and

Buddy Childers had an event

Contemporary Concepts Presented - A 4 Day Jazz Festival Celebrating The West Coast Big Band Sound in Concert in Los Angeles, California. Speakers/Panelists included Russell Garcia, Buddy Childers,

Pete Rugolo, and

Allyn Ferguson.

[4]

On 27 May 2005 the L.A. Jazz Institute honored Garcia for his more

than 60 years of contributions to jazz. The evening was hosted by

Tierney Sutton and guest speakers included

Bill Holman (musician), Duane Tatro and

Bud Shank.

[5] Charmed Life: Shaynee Rainbolt Sings Russell Garcia is a recent CD release featuring his work in collaboration.

[2]

Russell and Gina Garcia both received the 2009 Queen's Service Medal for New Zealand for their service to music.

[6]

Professional career

When he was eleven years old, the Oakland Symphony Orchestra

performed his arrangement of "Stardust". By the time Garcia was in high

school, he was working five nights a week playing music and earning more

than his father who was a credit manager in a large department store.

After one year at

San Francisco State University,

he dropped out because he felt he was not learning enough and instead,

went on the road with several big bands. But he remained unsatisfied,

because he says “I wasn’t advancing fast enough.” He recalled, “I quit

and went to Hollywood and had lessons with the best teachers I could

find.” He studied composition, harmony, orchestration, counterpoint and

form. He took lessons on every instrument so he could write for each

with a deeper awareness, rather than just by ear as he had done in the

past. He also conducted the West Hollywood Symphony Orchestra once a

week for two years, a remarkable experience for a young man in his 20’s,

and he says it primed him for what was to come.

His first break came in 1939, when the composer/conductor of the radio show

This is Our America fell ill and Garcia was recommended to fill in. He so impressed the director,

Ronald Reagan, that he was kept on for two years. Reagan was then married to

Jane Wyman

who recommended Garcia to NBC where he was hired as a staff composer

and arranger. As word got out, he says he never had to look for work:

“It’s always come to me. I do lead a charmed life.” Soon after

Henry Mancini called on Garcia and his extraordinary talent of transcribing note for note, instrument for instrument, to work on

The Glenn Miller Story.

Charlie Chaplin hired him to do all the arrangements for

Limelight,

and Universal Studios contracted him to work as composer, arranger and

conductor. He remained in the post for 15 years. In 1957 when an

arranger/conductor was needed for a Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald

record album

Porgy And Bess, Garcia was hired. It is still an international best seller.

[citation needed] He undertook three more albums and a concert at the

Hollywood Bowl with Armstrong.

Bethlehem Records

often called on Garcia’s arranging abilities since he was one of the

few Hollywood soundstage and studio veterans who could easily and

naturally switch from film scoring to jazz arranging without missing a

beat.

[2]

Developing a parallel career, not only did he provide arrangements for

many singers and instrumentalists, he recorded over 60 albums under his

own name, as well as composing for cutting edge projects such as the

Stan Kenton Neophonic Orchestra.

He has always been an innovator with his music using experimental

frameworks on which newer and greater presentations could be fashioned,

as he proved, assembling his unexpected and groundbreaking four-trombone

band

[7] with brass players

Frank Rosolino,

Tommy Pederson,

Maynard Ferguson and

Herbie Harper.

Marty Paich

can even be heard on some of these sessions at the piano. He used this

instrumentation and sound to great success in collaborations with

singers like Frances Faye and Anita O’Day, and now brings it back to us

in his most recent collaboration: a recording of all Garcia originals

with New York vocalist, Shaynee Rainbolt.

[8]

Yet even though he loved what he was doing, in 1966 he decided to walk away from it all. “I fought in the

Battle of the Bulge

during World War II and vowed that if I ever got out of it alive, I was

going to dedicate myself to world peace.” The Garcia’s decided to sail

the Pacific Ocean, carrying the message of peace and the Bahá'í Faith to

the remote islands of the South Pacific. Garcia said, “Not many people

have the chance to follow their hearts with no financial worries. We had

the “charm” working for us: we knew the royalties would see us through

for some years.” They spent the next six years on their 13-metre

fiberglass trimaran the Dawn-Breaker, as “traveling teachers,” anchoring

in such exotic locations as Jamaica, the Galapagos Islands, the

Marquesas and Tahiti.

In Fiji, in 1969, the “charm” spun again when musicians visiting from

Auckland invited Garcia, on behalf of the New Zealand Broadcasting

Commission and the Music Trades Association, to do live concerts, radio

and TV shows as well as lecture at universities around the country, a

perfect fit seeing as Garcia is also known in music circles as the

author of what are considered the definitive textbooks on composition:

The Professional Arranger Composer Books I and II. They have been translated into six languages and are used in universities and conservatories around the world.

His music

His Baha'i music includes the music (and non scripture lyrics) for

1960s and 1970s songs "One Heart Ruby Red" (with Donna Taylor),

"Nightingale of Paradise" (with Gina Garcia), "Hollow Reed", "We Will

Have One World", "The Hatin' Wall" (with Donna Taylor), "Live in the

Glory" (with Dorothy Wayne), "Hidden Words", and "Into Parched and Arid

Wastelands"

[10]

-

- Note: This discography is incomplete

To see more of who died in 2011

click here