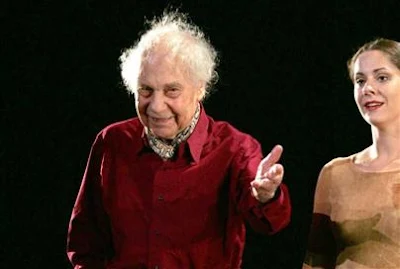

Mercier (Merce) Philip Cunningham died he 90. Cunningham was an American choreographer who was at the forefront of the American avant-garde for more than 50 years. Throughout much of his life, Cunningham was also considered one of the greatest American dancers. A constant collaborator who has influenced artists across disciplines—including musicians John Cage and David Tudor, artists Robert Rauschenberg and Bruce Nauman, designer Romeo Gigli, and architect Benedetta Tagliabue—Cunningham’s impact extends beyond the dance world to the arts as a whole.

Mercier (Merce) Philip Cunningham died he 90. Cunningham was an American choreographer who was at the forefront of the American avant-garde for more than 50 years. Throughout much of his life, Cunningham was also considered one of the greatest American dancers. A constant collaborator who has influenced artists across disciplines—including musicians John Cage and David Tudor, artists Robert Rauschenberg and Bruce Nauman, designer Romeo Gigli, and architect Benedetta Tagliabue—Cunningham’s impact extends beyond the dance world to the arts as a whole. (April 16, 1919 – July 26, 2009)

As a choreographer, teacher,  and leader of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Cunningham had a profound influence on modern dance. Many dancers who trained with Cunningham formed their own companies, and they include Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Karole Armitage, Foofwa d’Immobilité, Kimberly Bartosik, and Jonah Bokaer.

and leader of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Cunningham had a profound influence on modern dance. Many dancers who trained with Cunningham formed their own companies, and they include Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Karole Armitage, Foofwa d’Immobilité, Kimberly Bartosik, and Jonah Bokaer.

In April 2009, Cunningham celebrated his 90th birthday with the premiere of a new work, Nearly Ninety, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York. Also in 2009, the Cunningham Dance Foundation announced the Legacy Plan, a precedent-setting plan for the continuation of Cunningham’s work and the celebration and preservation of his artistic legacy.

Cunningham earned some of the highest honors bestowed in the arts, including the National Medal of Arts and the MacArthur Fellowship. He also received Japan's Praemium Imperiale, a British Laurence Olivier Award, and was named Officier of the Légion d'honneur in France.

Cunningham’s life and artistic vision have been the subject of numerous books, films, and exhibitions, and his works have been presented by groups including the Ballet of the Paris Opéra, New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, White Oak Dance Project, and London'sMerce Cunningham was born in Centralia, Washington in 1919, the second of three sons. Both his brothers followed their father into the legal profession. Cunningham initially asked to attend dance school when he was ten years old, and received his first formal dance and theater training at the Cornish School (now Cornish College of the Arts) in Seattle, which he attended from 1937-1939. During this time, Martha Graham saw Cunningham dance and invited him to join her company.[1]

In the fall of 1939, Cunningham moved to New York and began a six year career as a soloist in the company of Martha Graham. He presented his first solo concert in New York in April 1944 with composer John Cage, who became his life partner and frequent collaborator until Cage's death in 1992.

In the summer of 1953, as a teacher in residence at Black Mountain College, Cunningham formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company as a forum to explore his new ideas on dance and the performing arts.

Over the course of his career, Cunningham choreographed more than 200 dances and over 800 “Events,” which are site-specific choreographic works. In addition to his role as choreographer, Cunningham performed as a dancer in his company into the early 1990s.

Over the course of his career, Cunningham choreographed more than 200 dances and over 800 “Events,” which are site-specific choreographic works. In addition to his role as choreographer, Cunningham performed as a dancer in his company into the early 1990s.

He continued to lead his dance company until his death, and presented a new work, Nearly Ninety, in April 2009, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York, to mark his 90th birthday.[2]

Cunningham lived in New York City, and was Artistic Director of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cunningham died peacefully in his home on July 26, 2009.[3]